One of my very first sports obsessions was tennis. I grew up watching Billie Jean, Chrissy, Martina, Arthur, John, Jimmy, and others. I begin each year watching the Australian Open, then on to Roland Garros and Wimbledon, and finish with the US Open. But now, I am reconsidering my participation as a fan.

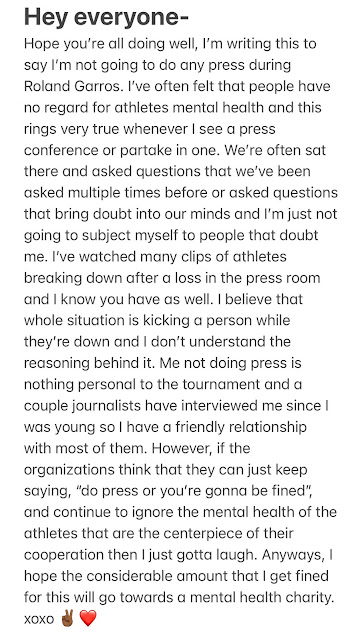

Naomi Osaka, the number 2 seed at Roland Garros, announced before this year's tournament began that she was going to opt out of the mandatory press sessions which follow each match, to preserve her mental health.

(@naomiosaka, May 26, 2021)

With the increasing emphasis in popular media on mental health, her understanding of her own needs and recognition of what she should do to maintain her health shows this to be an appropriate decision. However, the folks in charge responded by muttering something that was vaguely supportive, and then began clutching their pearls and reminding her of her contractual obligations as a player, issuing stern warnings that she would be fined every time she does not meet with the press - what appeared to be a potential financial penalty of $140,000, if she continued through to the final round. Her response was to acknowledge her acceptance of the penalties, and to offer the suggestion that the revenue from the fines could be directed to a mental health charity.

After winning her first round match in France, she spoke briefly with the reporter on the court (the conversation is amplified though speakers so the crowd can hear from the winner and be acknowledged by them). But she did not attend the press conference. And she was fined $15,000, and was warned of possible escalating penalties in addition to the fines.

"(Naomi) Osaka, who said she expected to be fined for not speaking to the media, was assessed a $15,000 fine for her actions Sunday. She was also warned about the consequences of continuing her media blackout, which involve not just greater fines, but also tournament defaults and possible Grand Slam suspensions.

We have advised Naomi Osaka that should she continue to ignore her media obligations during the tournament, she would be exposing herself to possible further Code of Conduct infringement consequences. As might be expected, repeat violations attract tougher sanctions including default from the tournament (Code of Conduct article III T.) and the trigger of a major offence investigation that could lead to more substantial fines and future Grand Slam suspensions (Code of Conduct article IV A.3.).

More and more high-profile people are opening up about their mental health challenges, including those in the world of professional sports. For example, when Kevin Love spoke publicly of the panic attack that he suffered during an NBA game in 2017, people praised his courage and offered support. Since then, he started the Kevin Love Fund that prioritizes mental wellness alongside physical health.

In watching some of the other first round matches that weekend I saw that Grigor Dimitrov was forced to retire from the tournament midway through the third set of his match against Marcos Giron, because of continuing problems with his back. Online sports sites reported his early exit as "unfortunate", with folks indicating concern and compassion toward an athlete who is facing physical struggles. And yet, when an athlete made a proactive decision to preserve her mental health, those in charge of the event chose to pay muted lip service of support while loudly reminding her of the status quo, which is to require all participants to face not only the opponents on the court but also the often barbed interrogation of reporters who frequently question the athletes about their "grit", "focus", "resolve", and so on.

Then, on May 31, this post appeared on Instagram:

This isn’t a situation I ever imagined or intended when I posted a few days ago. I think now the best thing for the tournament, the other players and my well-being is that I withdraw so that everyone can get back to focusing on the tennis going on in Paris. I never wanted to be a distraction and I accept that my timing was not ideal and my message could have been clearer. More importantly would never trivialize mental health or use the term lightly. The truth is that I have suffered long bouts of depression since the US Open in 2018 and I have had a really hard time coping with that. Anyone that knows me knows I'm introverted, and anyone that has seen me at the tournaments will notice that I'm often wearing headphones as that helps dull my social anxiety. Though the tennis press has always been kind to me (and I wanna apologize especially to all the cool journalists who I may have hurt), I am not a natural public speaker and get huge waves of anxiety before I speak to the world’s media. I get really nervous and find it stressful to always try to engage and give you the best answers I can. So here in Paris I was already feeling vulnerable and anxious so I thought it was better to exercise self-care and skip the press conferences. I announced it pre-emptively because I do feel like the rules are quite outdated in parts and I wanted to highlight that. I wrote privately to the tournament apologising and saying that I would be more than happy to speak with them after the tournament as Slams are intense. I'm gonna take some time away from the court now, but when the time is right I really want to work with the Tour to discuss ways we can make things better for the players, press and fans.